5 min read

Employment Screening FAQ Series: Can We Consider Arrest Records in Hiring Decisions?

![]() AccuSourceHR, Inc.

:

Apr 3, 2019 11:00:08 PM

AccuSourceHR, Inc.

:

Apr 3, 2019 11:00:08 PM

When you’re trying to make the best possible hiring decision, criminal records are often considered an important source of information. If you want to know as much about a person’s background as you can, including if someone has a history of criminal activity, you’re not alone. Ninety-six percent of US employers perform background checks, according to a recent study by HR.com and the PBSA.

But is there a limit to what you should consider?

Today we continue our employment screening FAQ series with a question about a particular type of criminal record history–arrest records.

Question: Can I consider an applicant’s arrest record when making a hiring decision?

Answer: In general, you may use arrest records, but there is a right way and a wrong way to do so.

One of the cornerstones of the United States Constitution is “innocent until proven guilty.” The presumption of innocence has its roots in three different Bill of Rights Amendments (the 5th, 6th and 14th, if you’re curious!).

As an employer, you may lawfully treat conviction records as proof that the person engaged in the unlawful activity he or she was convicted of, but under the federal equal opportunity law, you may not lawfully treat an arrest that did not result in a conviction the same as a conviction. In most cases, you are not allowed to deny employment or take adverse action against an applicant based on an arrest record by itself. You must also independently determine whether or not the individual actually engaged in the unlawful activity he or she was arrested for.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) guidelines on the use of arrest and conviction records underscore why: “The fact that an individual was arrested is not proof that he engaged in criminal conduct.”

Let’s take a deeper dive into the challenges arrest records pose.

Arrest Record Shortcomings

Sheer Quantity

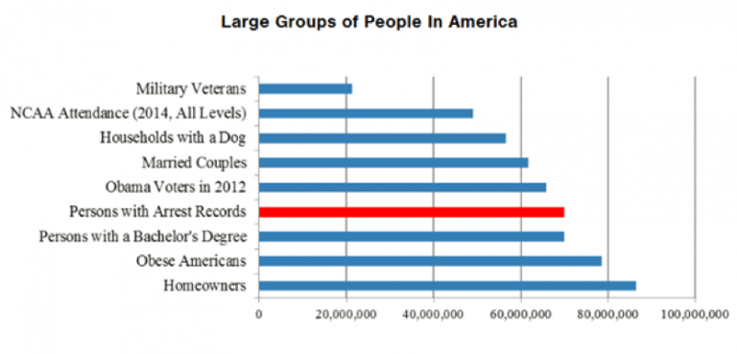

The FBI maintains a national index of criminal histories, available to all law enforcement agencies but not available to most employers, called the Interstate Identification Index (III). It contains arrest records of more than 70 million Americans. As a frame of reference, that is the same number of Americans who have college bachelors’ degrees. If all arrested Americans formed a nation, they would be about the size of France, Germany, or Thailand.

Just under a third of the people in the database, 20 million, have felony convictions. The remaining 50+ million were never charged with crimes, had the charges dropped, were never convicted, or were convicted of misdemeanors.

Source: BrennanCenter.org

Even when someone is arrested and found not guilty, their arrest can remain on the record unless they have it sealed or expunged.

Here is an example from the EEOC’s Guidance on the Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records:

Example: Arrest Record Is Not Grounds for Exclusion. Mervin and Karen, a middle-aged African American couple, are driving to church in a predominantly white town. An officer stops them and interrogates them about their destination. When Mervin becomes annoyed and comments that his offense is simply “driving while Black,” the officer arrests him for disorderly conduct. The prosecutor decides not to file charges against Mervin, but the arrest remains in the police department’s database and is reported in a background check when Mervin applies with his employer of fifteen years for a promotion to an executive position. The employer’s practice is to deny such promotions to individuals with arrest records, even without a conviction, because it views an arrest record as an indicator of untrustworthiness and irresponsibility. If Mervin filed a Title VII charge based on these facts, and disparate impact based on race were established, the EEOC would find reasonable cause to believe that his employer violated Title VII.

Missing Arrest Disposition Records

A disposition is the final outcome of an arrest. It reports whether the arrested person was charged or not, brought to trial or not, and whether the charge resulted in a conviction, acquittal or dismissal. The final disposition is entered into the court record and posted by a clerk.

A court’s criminal records should include a record of the final disposition of each arrest, however, not all are up to date. The result is that many arrest records in the various law enforcement agency databases are not associated with a final disposition, and therefore require further inquiry or verification.

Perception Equals Reality for Many

Any arrest comes with its own sentence, whether the party was guilty or not. That “sentence” is the subtle change in perception even the most well-meaning employer experiences upon learning of a candidate’s arrest record. The Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) surveyed employers and found 31 percent of respondents said an arrest without conviction would at least be “somewhat influential” in their hiring decision. Legal or not, perception is often reality. Even a hint of malfeasance can be enough to tip the scales against a candidate.

How to Lawfully use an Arrest Record

Some states, including Illinois, Pennsylvania, and California, forbid employers from asking about arrests that did not lead to a conviction. At the federal level, the EEOC guidelines also dictate that employers cannot reject an applicant outright based solely on an arrest record. However, there are circumstances in which an arrest may be lawfully used in an employment decision.

Here is an example from the EEOC’s Guidance on the Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records:

Example: Employer’s Inquiry into Conduct Underlying Arrest. Andrew, a Latino man, worked as an assistant principal in Elementary School for several years. After several ten and eleven-year-old girls attending the school accused him of touching them inappropriately on the chest, Andrew was arrested and charged with several counts of endangering the welfare of children and sexual abuse. Elementary School has a policy that requires suspension or termination of any employee who the school believes engaged in conduct that impacts the health or safety of the students. After learning of the accusations, the school immediately places Andrew on unpaid administrative leave pending an investigation. In the course of its investigation, the school provides Andrew a chance to explain the events and circumstances that led to his arrest. Andrew denies the allegations, saying that he may have brushed up against the girls in the crowded hallways or lunchroom, but that he doesn’t really remember the incidents and does not have regular contact with any of the girls. The school also talks with the girls, and several of them recount touching in crowded situations. The school does not find Andrew’s explanation credible. Based on Andrew’s conduct, the school terminates his employment pursuant to its policy.

Andrew challenges the policy as discriminatory under Title VII. He asserts that it has a disparate impact based on national origin and that his employer may not suspend or terminate him based solely on an arrest without a conviction because he is innocent until proven guilty. After confirming that an arrest policy would have a disparate impact based on national origin, the EEOC concludes that no discrimination occurred. The school’s policy is linked to conduct that is relevant to the particular jobs at issue, and the exclusion is made based on descriptions of the underlying conduct, not the fact of the arrest. The Commission finds no reasonable cause to believe Title VII was violated.

In these cases, the employer investigates the conduct leading to the arrest to determine whether it presents grounds to exclude a candidate. Further, the employer must ascertain whether the conduct in question would make the candidate a greater risk in that specific job than another candidate.

To complicate matters, certain state statues that require checks of law enforcement agency arrest databases for specific roles – such as police officers, teachers, TNC drivers, financial services, etc. – may be required to be followed to satisfy your state law requirements. This is even while the EEOC has stated that such a practice might not be in line with equal opportunity law. Situations like these can put employers in a precarious position.

The employer needs to carefully evaluate whether the conduct exclusion is job-related and consistent with business necessity. The EEOC Uniform Guide describes three Green Factors used to make that determination:

- the nature and gravity of the offense;

- the time that has passed since the conviction or conduct; and

- the nature of the job held or sought.

As always, the employer should give the applicant an opportunity to refute or explain the circumstances of the arrest before finalizing the decision.

A Final Reminder

Arrests are not proof of bad behavior, nor are they even necessarily indicative of a person’s character. Every job applicant should be treated fairly and assessed individually. Employers should use arrest records very carefully, if at all.

If you have questions about the use of criminal records in the hiring process, please contact us. We’d love to help you navigate through these issues. And of course, we strongly suggest you consult with an experienced employment law attorney with respect to these complicated and nuanced issues.